The Partisans

Partisans

Partisan experience told by the museum describes the struggle of an entire community: guerrilla warfare, actions in the mountains and hills, clandestine life and sabotages. Museum gives an account of the actions of the partisans in this area, which moved from hills to lowland and valleys and needed to create a network of collaboration and trust with civilians. Here added together the experience of men and the will of youth who were learning to fight, the strength of women and the courage of girls who became “staffettePeople who had the mission of carrying news and items from one area… More”, partisans’ couriers and helper.

Talk about the Resistance struggle in Romagna means describing a broad mass movement, where the support and collaboration of the lower social classes were decisive. In the autumn of 1944, the war front arrived and the alliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More troops, who supplied weapons, uniforms and food, established a collaboration with the men and women of the country, holders of an accurate and precious knowledge of the land.

The first partisan groups were already born in the autumn-winter of 1943 in the Romagna Apennines, in opposition to fascismItalian political movement founded by Benito Mussolini in 1919, inspired by the Fasces… More. They were formed largely by young people determined not to respond to the call to arms of the R.S.I. In February of 1944, the groups turned into real brigades and this is an important period for the self-determination of Resistance, but also difficult and dangerous because of the vast roundups by the Germans. The struggle in the lowlands developed in that time too: the guerrilla warfare practiced on the Apennines here was more insecure, due to the continuous movements without safe natural hiding places, so the cooperation with workers and sharecroppers became fundamental, providing shelters and houses for the Liberation struggle.

In the summer of 1944 in Ravenna began an intense activity against Germans and fascists from the population of the countryside. In the imminence of the decisive clash, Germans and fascists tried to seize all the resources of the land and the population made a lot of actions, including sabotageAttacks carried out by partisans with guerrilla techniques to reduce the enemy’s war… More, especially along the main roads (State Road 16, Emilia Road and San Vitale Road) and along the railway line where German convoys were continuously attacked and damaged.

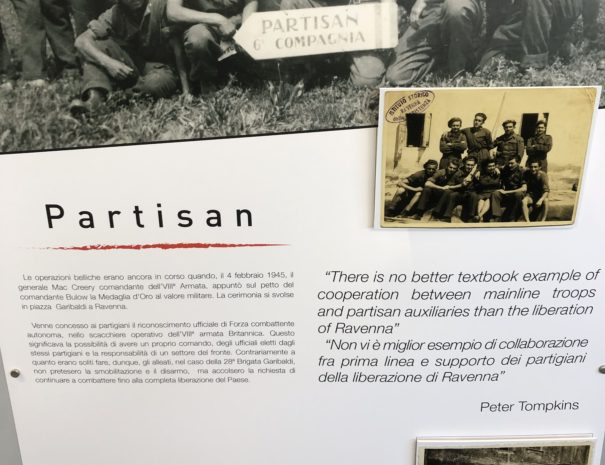

In the twenty months of Resistance, the fighters went from defectors to fascist mandatory military service to guerrillas, from “banditen” to regular soldiers in the AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More army ranks. The qualification of “Partisan” is the final acknowledgement and the result of social conditions never seen before.

Towards the end of the summer of 1944, the farmers of Ravenna have exposed themselves in many guerrilla actions and it seems that the arrival of the Allies is imminent, but the announcement of Alexander’s proclamation, in November 1944, declares all AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More military operations suspended for the winter and comes like a bolt from the blue.

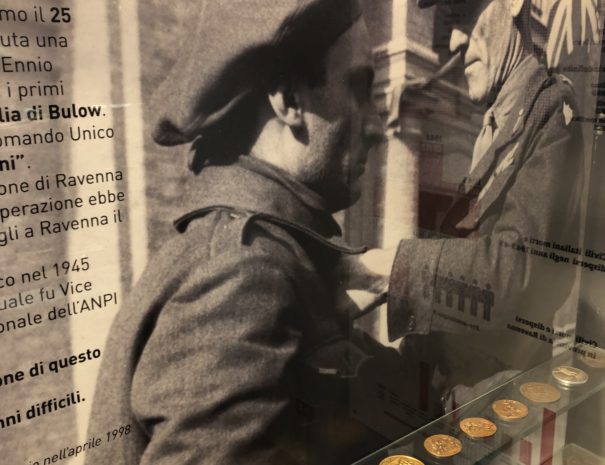

The 28th Garibaldi Brigade, named “Mario Gordini”, one of the best organized partisan formations of the entire Italian Resistance, operates on this territory and is divided into detachments each of which competed for a different field of operations. Commander of the brigade is Arrigo BoldriniAnti-fascist militant coming from Ravenna, after September 8, 1943, he was one of… More (nom de guerre Bulow), elected in June 1944 and appointed liaison officer between the brigades of Romagna and the CUMERCommand of Volunteer Freedom Corps (CVL) established at the beginning of July 1944… More (the military Command of Emilia-Romagna).

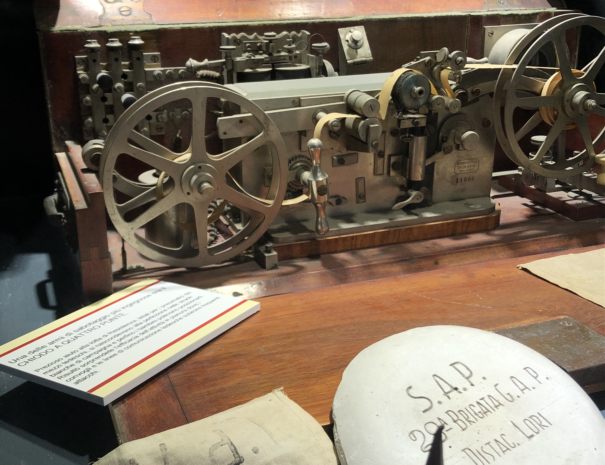

In the north of Ravenna, at the Canna Valley, there is an island, “Spinaroni island”, where was established a permanent partisan base and was located the detachment named “Terzo Lori”. Thanks to a rich vegetation, typical of marshy areas, and the complicity of the inhabitants of the surrounding, hundreds of partisan fighters remain hidden from the eyes of the enemy. There, partisans who need a safe place find shelter and the island has also strategic importance because from there start the night attacks to the German garrison and it was possible to control a vital stretch of the State Road 16. The AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More send there with airdrops weapons and a radio set, to provide valuable signals to the AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More Command for the advance of the Canadians on Ravenna.

In December 1944 over six hundred partisans were mobilized from here for the Battle of the Valleys, which allowed the AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More army to easily enter in Ravenna for the final liberation. At the beginning of autumn, in fact, all the partisan forces in the area, commanded by Bulow, are aware of the impossibility of remaining stationary until the arrival of spring and plan for the liberation of Ravenna. It involved partisan forces assisted by the Porter Force and the men of commander Vladimir Peniakoff. The action has a happy outcome: the liberation of the city on December 4, 1944. In the following days and nights a difficult battle took place in the valleys, that led to the liberation of Porto Corsini, Faenza and Bagnacavallo (21 December 1944).

On February 4, 1945, in Ravenna, Bulow was decorated with the Gold Medal for Military Valor for the operations that led to the liberation of the city, and his men were equipped as soldiers, militarily framed and could participate, on the front line, in the Battle of the Senio. To the partisans of the 28th Garibaldi Brigade was in fact granted the official recognition of autonomous fighting force within the British VIII Army, contrary to what usually happened (disarmament and demobilization once the reference territory was liberated).

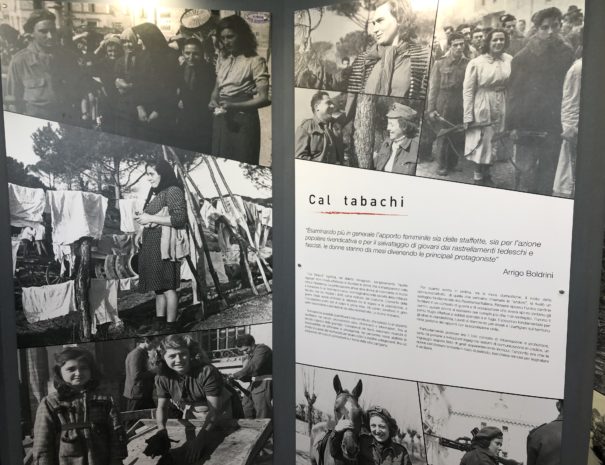

“Examining more generally the female contribution of staffette, popular actions claimed and the rescue of young people from German and fascist roundups, by months women have been becoming the main protagonists “.

This is how Arrigo BoldriniAnti-fascist militant coming from Ravenna, after September 8, 1943, he was one of… More comments on the range of women’s action in defining the fate of the war still in progress. It will never be possible to quantify the contribution of women in the Resistance struggle.

The occupation of the region brought civilians to the forefront, and while men were forced to live in hiding, women remained. “Cal tabachi”, “those girls” in Romagna dialect, is how were called the girls actively involving alongside the partisans. The participation of women was a new phenomenon, unimaginable during the fascist era: aware of the risks, they made themselves available for the logistical service of the guerrillas and assumed positions of various responsibilities, up to working in the role of combatants on the front of the partisan struggle.

When the partisans move towards the lowlands, the contribution of families becomes indispensable because they must hide themselves in the peasant houses, families provide them food and clothing and carry their messages from one base to another. Here the work of the staffettePeople who had the mission of carrying news and items from one area… More becomes essential: generally young girls, who delivers orders and messages but also weapons, ammunition and clandestine pressNewspapers and leaflets printed and distributed illegally to the various partisan groups by… More, often traveling several dozen miles on bicycles and always with the fear of searches at checkpoints.

In the countryside of Ravenna the contribution of the “adzore” was of primary importance too: in absence of men, engaged at the front, prisoners or active in the clandestine struggle, the women, become “heads of families”, hold the fate of the house. They took important and heavy decisions in helping and protecting the fighters of the Resistance. Information and protection were in fact their tasks, and over time they created several coded communication systems, apparently harmless, such as the choice of linen to hang according to the message to be transmitted to the partisans.

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua

La Battaglia del Senio

“Tutto l’orizzonte orientale era una massa di rumori. I proiettili producevano un’infinita gamma di effetti sonori: quelli da 25 libbre sfrecciavano con il rumore di una grande tenda lacerata, mentre i 4,5 e i 5,5 fendevano l’aria come treni lanciati a tutta velocità che passavano sopra le nostre teste e piombavano sull’argine. A volte il fragore diventava più aspro, come se il cielo fosse un’immensa porta d’acciaio sbattuta in faccia al nemico… Sembrava impossibile che tutto quel baccano provenisse da una fonte invisibile e si alzava lo sguardo come aspettandosi di veder il cielo lacerato e dilaniato dai proiettili di passaggio, proprio come li mostrano i disegnatori di fumetti. Ma non c’era niente, tranne la foschia e gli aerei che volavano in cerchio.” John Ellis, The Sharp End of the War

Ancora oggi, ogni paese lungo il corso del fiume trattiene il ricordo della battaglia sul fronte del fiume Senio e dei combattenti che ridettero loro la libertà: nei primi giorni di aprile del 1945 soldati di cinque continenti, riuniti nell’Ottava Armata britannica, insieme ad Italiani dell’Esercito regolare e a partigiani volontari, sconfissero le ultime difese dei tedeschi e dei fascisti della R.S.I., ponendo fine alla campagna d’Italia. Eserciti di oltre venti nazioni si scontrarono, dalla Nuova Zelanda all’India, dalla Polonia al Canada e al Nepal (i Gurkha). Assieme all’esercito alleato la presenza dei reparti del nuovo Esercito italiano, all’interno dei quali erano numerosi anche gli ex partigiani volontari dell’Italia centrale.

Dalla foce del Senio nel Reno fino al mare furono invece i partigiani della 28° Brigata Garibaldi, riconosciuti come unità combattente dagli Alleati, a guidare le operazioni lungo la costa adriatica, fin nel cuore del Veneto.

Il Gruppo di Combattimento Cremona

Il 10 aprile 1945 protagonisti della liberazione di alfonsine furono i fanti del Gruppo di combattimento Cremona: soldati del nuovo esercito italiano, per la maggior parte ex partigiani.

Nel luglio del 1944 lo Stato Maggiore Italiano istituì due gruppi di combattimento, con uomini dalle divisioni “Cremona” e “Friuli”, reduci dalla liberazione della Corsica e della Sardegna e richiamati sul continente per essere inquadrati nelle fila dell’VIII armata britannica.

Guidato dal Generale Clemente Primieri, il GdC “Cremona” poteva contare su quasi 10.000 soldati, con i reparti 21° e 22° fanteria e 7° artiglieria e un battaglione del Genio, a cui si aggiunsero man mano centinaia di volontari ed ex partigiani che provenivano dalle zone liberate di Marche, Toscana e Umbria. L’arruolamento di questi ultimi in particolare, nonostante le opinioni divergenti dell’esercito alleato rispetto al regio esercito, era infatti necessario per compensare le formazioni regolari che si trovavano sottonumero.

Nel nostro territorio il “Cremona” aveva il compito di scardinare le difese tedesche e fin dai primi giorni dovette sostenere violenti attacchi. Durante l’operazione Sonia in particolare, che ha portato alla liberazione dei territori sul Senio tra cui Alfonsine, dovevano attraversare il fiume e garantire una testa di ponte lungo la statale 16 adriatica: alle 5.25 del 10 aprile 1945 i Cremonini forzarono il Senio, conquistando Alfonsine e Fusignano e salvando così da morte certa molti abitanti dei due paesi; se non fossero riusciti nell’impresa infatti, gli Alleati avrebbero utilizzato l’artiglieria pesante per garantirsi un varco.

Le perdite subite dal Gruppo di Combattimento “Cremona” ammontano a 178, mentre 605 rimasero feriti e 80 furono i dispersi. Le spoglie dei Caduti sono conservate nel Sacrario di Camerlona (RA) a loro dedicato e gli abitanti dei paesi liberati dall’occupazione nazifascista mantengono ancora oggi saldi legami di amicizia con quelli di provenienza dei combattenti.