The Enviroment

A changing landscape

When the war erases a city and moves another to the opposite side of the river.

Vladimir Peniakoff (Popski) says about the Po Valley that the enviroment, intersected by a network of rivers and drainage canals, deeply embedded between banks sometimes up to 15 meters high, was even less suitable for German pursuit than the mountainous regions. The Allies made an erroneous assessment of the Po Valley, considering on paper to advance with heavy armoured vehicles.

Instead, in field, it resulted the marsch destined to sink the momentum of the attack in the autumn of 1944, leading to a drastic slowdown of military operations and a stalemate of the front line throughout the winter between ’44 and ’45.

Romagna’s environment at the time of the war was characterized by muddy reclaimed marshes and the road to Bologna was long and crossed by innumerable rivers which, starting from September, swelled dramatically due to the autumn rains making the land almost impassable.

Romagna’s environment at the time of the war was characterized by muddy reclaimed marshes and the road to Bologna was long and crossed by innumerable rivers which, starting from September, swelled dramatically due to the autumn rains making the land almost impassable.

Eric Morris describes in this way the land in his book “Circles of Hell: The War in Italy 1943-1945”.

The autumn and winter between 1944 and 1945 were particularly inclement months, the rains were three times more abundant than usual. The Romagna environment, however, was not only difficult to deal with due to adverse weather conditions, but due to human action too: the changes, often sudden and violent, caused by events such as bombings, mining or flooding of the countryside, have a big impact in everyday life. Germans during the last months mined the fields and pierced the banks flooding the countryside, to slow down the AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More advance, while the Allies bombed the inhabited centres to eliminate as many Germans as possible.

In the winter of 1944, the area marked by the course of the river Senio between Castel Bolognese, Cotignola and Alfonsine represented an area of great strategic importance, crossed by numerous rivers and important communication routes, such as the Via Emilia, the state road 253 called San Vitale and, in particular, the Adriatic State Road n. 16 which was the only way to Ferrara and Padua after the flooding of the Valleys of Comacchio and Campotto by the Germans, in an attempt to restrict the territory to defend.

For four months, this area was characterized by the presence of the front, overcome with the Allied offensive between 9 and 12 April 1945 which took the name of “Battle of the Senio”, an offensive that ended the war in Romagna and, over the course of two weeks, throughout Italy. The clashes of those days deeply marked the territories located along the river and the most affected areas were Alfonsine, Fusignano, Cotignola, Solarolo, Castel Bolognese and Riolo dei Bagni, where there was a very high number of civilian victims due to prolonged fighting, AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More aerial bombardments and lots of mines left on the ground by the Germans.

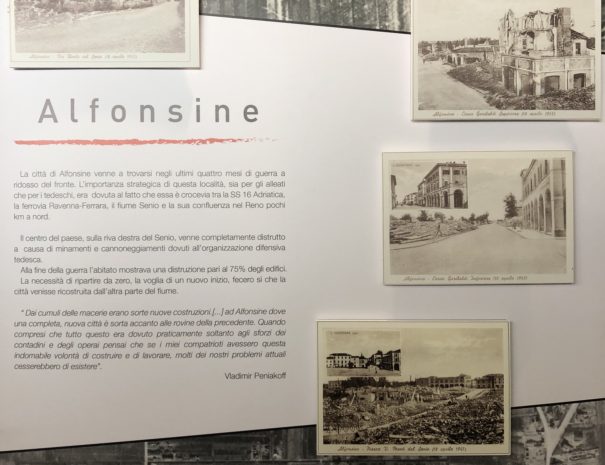

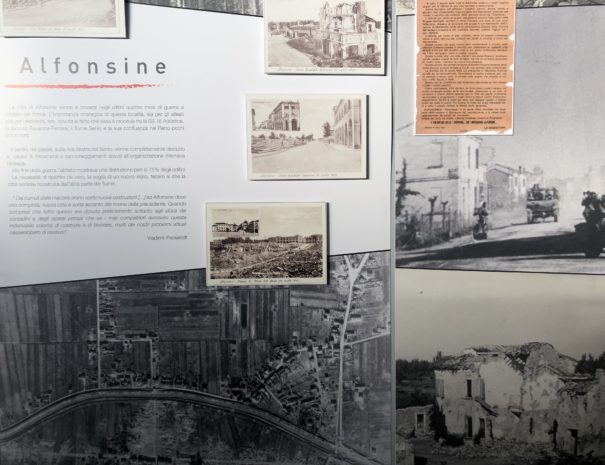

Among the towns hit by this disaster, the municipalities of Alfonsine, Fusignano and Cotignola were the most affected. Alfonsine – which was located in a particularly critical point at the intersection of the State Road 16 and the Senio river – preserves the most painful memory: the inhabited centre completely lost its physiognomy due to the AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More bombings and explosions caused by the retreating Germans, and the enormity of the damage made it necessary to completely rebuild the town beyond the opposite bank of the Senio river.

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum

Cras nec consequat neque, nec placerat purus. Maecenas dui turpis, suscipit vel.

Lorem ipsum

Maecenas nibh ipsum, viverra faucibus consectetur non, maximus id ante.

Lorem ipsum

Nullam faucibus pretium augue in iaculis. In leo dui, molestie vel congue in, viverra in.

Lorem ipsum

Duis posuere hendrerit mi et tincidunt. Aliquam est est, rhoncus sit amet massa at, element.

Lorem ipsum

Fusce in condimentum dolor. Donec quis pharetra nulla. Nam efficitur tortor sit amet.

Lorem ipsum

A lacinia elit, in malesuada orci. Nam imperdiet risus ut eleifend sodales. Phasellus dolor.

The context in which civilians and soldiers moved was a very backward world compared to what we are used to now: the roads, except for State Road 16, were generally gravel roads and, in the winter months, reduced to muddy stripes. Transports were very small in number: German sidecars, some cars, military trucks and mostly bicycles, often shabby and without tires, replaced by ropes, generally not equipped with a headlight. The bicycle was, at the time, a real wealth for the family: it facilitated travel and allowed to go to work even in relatively distant areas and did not require food and care, as horses, donkeys and other animals used for transport.

The war worsened these conditions, adding mines and bombings that had as their first targets railway lines and the main communication routes. In floodplain there are also numerous streams within a short distance of each other and it is essential to use bridges: during the last months of the war many bridges were useless because they were blown up or mined to prevent the enemy from moving easily.

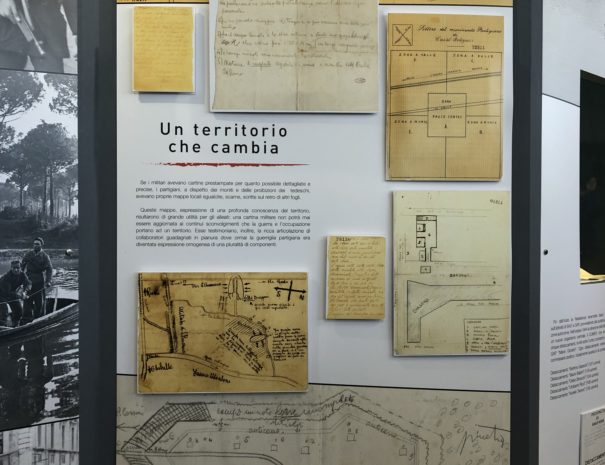

Exhibited in the Museum are several cartographic representations of the Ravenna territory, used by all the armies in field, testifying the fundamental attention that the soldiers placed in these tools to be able to operate in the valley environment.

The changes brought by the war and the uncontrollable presence of water, due to rains, ruin of the banks and distribution of the valleys, required continuous cartographic descriptions that indicated the variable depth of the seabed and the obstacles not visible with binoculars.

The knowledge of the landscape by the partisans was one of the basic reasons for the collaboration with the AlliedMilitary alliance formed by several states, mainly Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the… More army, which moved with heavy armoured vehicles and needed to protect itself from troubles that could not be reported on a map.